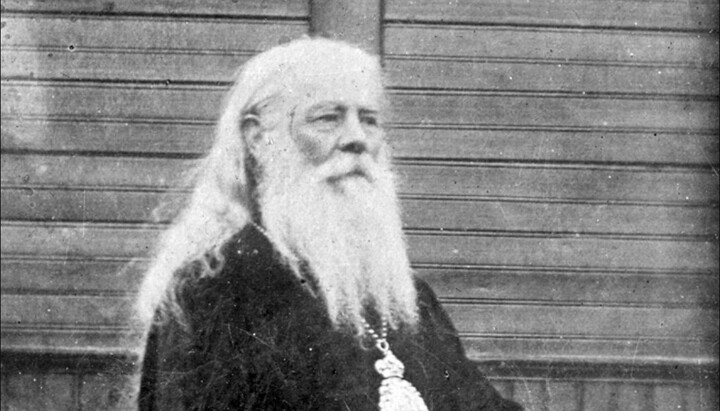

New martyrs of the 20th century: Hieromartyr Alexander of Kharkov

He was ordained to the priesthood relatively late, at the age of 49, and his episcopal ministry took place during the difficult 1930s. But all of this might never have happened...

Early Years

The future hierarch was born in 1851 in Lutsk to a deacon's family. His secular name was Alexander Theofanovich Petrovsky. Information about his life before 1899 is quite scarce. It is known that his father died early, that he finished 4 classes of the Volhynian Theological Seminary, and that from 1892 he taught at the parish school in the village of Kniaginino in the Dubno district. However, by 1892, he was already 41 years old. What he did after finishing the seminary, where he worked, what kind of life he led, whether he was married, or if he regularly attended church – unfortunately, we can only speculate on these matters.

It is known that he was very affectionate to his mother, who raised him without a father. But his mother also passed away, after which Alexander, as sources say, began to live a "dissipated life". The exact time of his mother's death and how long he led this "dissipated life" is unknown.

If we try to piece together a picture of his life from such little information, it might look something like this: since there is no information about Alexander having any siblings or a wife and children, it is likely that he lived alone with his mother. And since his father died early, his mother probably transferred all her maternal love and care to him alone, to which Alexander responded with the same strong affection and attachment.

This is usually what prevents an already grown man from starting his own family. Family psychologists are quite familiar with such cases. The "Italian mother" phenomenon falls into this category. But let’s not go too far into speculation. However, one point to focus on is that when his mother died, Alexander lost his closest and perhaps his only close person. This became such a heavy trial for him that he could not bear it and began to lead a "dissipated life", which could imply alcoholism and other vices. And this is already a very important spiritual moment.

In such trials, it is revealed what is most important for a person, without which they cannot live. If they lose it, they lose all life support and the very meaning of life.

In the life of Elder Varsonofy of Optina, who lived around the same time as St Alexander of Kharkov, there is a story about how, in his youth, he met a young woman who loved her fiancé very much. When he passed away, she mentally turned into a living corpse.

Already as an Elder, Varsonofy told his spiritual children: “If I met this girl now, I would know what to say to her. I would tell her: ‘Were you loved? From such love, only sorrow remains, only emptiness? And you say you won’t love anyone else? But I advise you to love another. Do you know who? The Lord Jesus Christ! You wanted to give your heart to a man – give it to Christ, and He will fill it with light and joy instead of the darkness and sorrow that remain from your love for a man.’”

The same was true in Alexander's life. After his mother's death, darkness and longing engulfed him. There are only two ways out of such a state: either to rise up to God or fall into the abyss of sin. Alexander chose the second path, but a miraculous vision of his deceased mother guided him toward the first.

One night, after another drunken binge, when he returned home late and lay down in his room, he saw a vision. His mother appeared to him and said, “Leave all this behind and enter a monastery.” And Alexander found the strength within himself to do just that.

Monasticism

On 1 September 1899, Alexander Petrovsky entered the Derman Holy Trinity Monastery and also began teaching at the local parish school. On 9 June 1900, he received the monastic tonsure, keeping his previous name. Just over a month later, on 15 August 1900, he was ordained as a hierodeacon. And another three months later, on 29 October 1900, he was ordained a hieromonk. At the same time, he immediately began to fulfil the highest obediences in the monastery – that of economist and sacristan. Starting from 18 November 1900, he also assumed the duties of the monastery's abbot.

Such a rapid "career rise" can be explained by the fact that, in those years, there were few educated people capable of taking on responsible roles in monasteries. The brotherhood was mainly made up of common folk, and their motivation for monastic life was, to put it mildly, varied. Later, Hieromonk Alexander was often transferred to different church positions, entrusted with responsible duties related to money and authority. This allows us to conclude that he was honest, conscientious and skilled in managing people.

In 1901, Hieromonk Alexander was transferred to the Kremenets Epiphany Monastery to serve as the treasurer. He also began teaching the Law of God in the parish school and became an active member of the Kremenets Holy Epiphany Brotherhood, which defended Orthodoxy from Catholicism and Uniatism.

Two years later, in 1903, he was sent as treasurer to the distant Eparchy of Turkestan. Soon this obedience was supplemented by participation in the eparchial school board and audit committee and the post of economist of the bishop's house. Not long after, he became a member of the spiritual consistory and treasurer of the missionary society. However, the local climate had a negative effect on Fr Alexander's health, and in February 1906, he was transferred to the Zhirovitsy Assumption Monastery, where he also became the treasurer and head of the two-class parish school.

Two years later came another notable transfer. In 1908, Hieromonk Alexander was moved to the stavropegial Don Monastery of Moscow as the acting abbot. This transfer is significant because, at that time, a serious conflict was broken out between the abbot, Archimandrite Jakob (Zablotsky), and the monastery's brotherhood. The church authorities attempted to resolve the conflict, but unsuccessfully.

It was then decided to send Archimandrite Jakob on leave, and to appoint Hieromonk Alexander as the acting abbot in his place. This is noteworthy because the Moscow church leadership could not find a suitable candidate locally and had to call the treasurer from a distant Belarusian monastery! This situation likely reflects both the seriousness of the conflict in the Don Monastery and Hieromonk Alexander’s authority in high church circles.

To this time belong the first surviving testimonies about Fr Alexander's character and his spiritual disposition. First, he was able to quickly find common ground with the brotherhood and resolve the conflict. Second, he began to root out improper behavior during the church services. For example, he insisted that there be no idle conversation or even confessions of pilgrims during the church services.

Here is one of Fr Alexander’s directives: "I ask the fathers in the altar, remembering the sanctity of the place, not to gather and engage in conversation, but to stand and sing in the choir, as was previously instructed."

From 1911 to 1917, Fr Alexander, by then elevated to the rank of hegumen, served as the abbot of the Savior Transfiguration Monastery of Lubny. During his time there, he was again described as a fervent prayerful leader, a diligent head of the monastery, and a caring pastor for both the brotherhood and the pilgrims. It was while serving in this capacity that the October Revolution of 1917 took place.

In December 1917, by then Archimandrite Alexander was appointed abbot of the Holy Assumption Pskovo-Pechersky Monastery. In 1918, he moved to Poltava, where he lived for a time with the local bishop, Feofan (Bystrov). In 1919, he became the abbot of the skete church of the Kozelshchina Women's Monastery on the Psel River in the Poltava Province. The main monastery had already been closed by the Bolsheviks, and the nuns had moved to the skete. For a time, a printing press and an icon-painting workshop operated there.

The services gathered a large number of people. Fr Alexander often encouraged the community to join in the singing during the services. The skete existed for quite some time, until 1932. After its closure, Fr Alexander moved to Kyiv, where he was appointed abbot of the St. Nocholas Monastery.

Bishopric and martyrdom

In those years, the words “bishopric” and “martyrdom” were almost synonymous. Bishops were shot, exiled and subjected to torture in prisons. It was on this path of the cross that Archimandrite Alexander embarked on 30 October 1932. On this day, he was consecrated as the Bishop of Uman, vicar of the Kyiv Eparchy. Then, on 25 August 1933, he was appointed Bishop of Vinnytsia. In 1937, he was elevated to the rank of Archbishop and appointed to the Kharkov See.

There are also preserved testimonies from those who lived through this period of his ministry. They noted the bishop’s sociability and friendliness. He also endeavored to impart to the faithful the high prayerfulness that he himself possessed. He also often urged those praying to sing together and taught them to pray not coldly and formally, but with a lively sense of standing before the Lord. Here are the words of the archbishop quoted by one of the witnesses: “You wouldn’t ask a person to give you something in such a cold way, would you? No one asks like that. Sing together: ‘Grant it, O Lord!’”

And the people, inspired by the example of their archpastor, asked God for mercy with all their hearts.

On 29 October 1937, Metropolitan Konstantin (Dyakov) of Kyiv was arrested in Kyiv; and on 10 November 1937, he suddenly died during interrogation. There are suspicions that he was either murdered or tortured to death. Under these circumstances, Archbishop Alexander was appointed as the temporary chancellor of the Kyiv Eparchy. This appointment, made at the peak of Stalin's purges, signified his imminent fate, and the archbishop understood this very well. At this time, he told his spiritual children: "Whatever happens next – hold on, be strong."

Then, events unfolded according to a scenario that bears striking similarities to the current persecution of the UOC. It turns out that persecutors can invent nothing new.

On 29 July 1938, Archbishop Alexander’s residence was searched. Several photographs, letters, a round seal, and several stamps were found. Such were the results of searches carried out in 2023 in the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra and other monasteries in Ukraine: the same meaningless "evidence" upon which very serious charges were nonetheless brought. Today, supporters of the UOC are accused of "anti-Ukrainian propaganda" and "discrediting the Orthodox Church of Ukraine" as an attribute of Ukrainian statehood. Archbishop Alexander, similarly, was accused of being "a member of an anti-Soviet church organization and conducting anti-Soviet agitation among the population aimed at discrediting Soviet government actions".

He was also charged with espionage on behalf of Poland, simply because he was born in Lutsk, which had been part of Poland since 1921. Naturally, he had relatives there with whom he maintained correspondence. And this became sufficient grounds for the accusation of espionage.

Just as today, the discovery of prayer books from Russian publishers serves as grounds for accusations of treason. History repeats itself.

Another episode from the investigation is also strikingly similar to what is happening now in Ukraine. In order to lend more credibility to the accusations, the investigators enlisted a certain K.A. Terletsky, who was a "deacon" from the Renovationist movement. This man, who had never even met Archbishop Alexander, slandered him by claiming that, "while performing religious rituals, he conducted anti-Soviet agitation among the faithful, telling them in his sermons that the existing regime in the USSR was allegedly a temporary phenomenon and that, in the very near future, fascist countries would attack the USSR, defeat it, and restore the monarchy. Petrovsky allegedly called on all clergy and believers to unite around the church to assist the fascist states".

This sounds similar to the claims made today by "experts" in the case of Orthodox journalists, Fr Serhiy Chertylin! They also claim that news materials are part of a "Russian information operation", and Fr Serhiy spoke about the "aggressive NATO" (though he actually spoke about 'ahresyvnyi NATOVP' – 'aggressive crowd' – Ed.).

But as the Holy Scriptures say, "Whoever digs a pit will fall into it, and whoever rolls a stone – it will come back on him" (Proverbs 26:27). Two years later, the repressive machine came for K.A. Terletsky himself. During one of his interrogations, he admitted that he had slandered Archbishop Alexander simply because the latter had called things by their true names, namely, that the Renovationist Church was a group of traitors to the Orthodox faith.

Archbishop Alexander did not escape the brutal methods used to get confessions: the nearly 90-year-old man was subjected to a "conveyor" interrogation process. This method involved multiple interrogators working for long hours, depriving the subject of sleep. There are testimonies that he was beaten during the interrogations. They demanded that he confess his guilt and also provide incriminating testimony against other clergy and believers, specifically targeting Archbishop Dimitry (Abashidze), who was living in Kyiv at the time.

Archbishop Alexander never confessed to any wrongdoing, nor did he betray others.

On 15 March 1939, the "Indictment" was issued, stating that Archbishop Alexander, along with other accused individuals, was a member of an "anti-Soviet, espionage-monarchist church organization" that "carried out espionage work for the Polish intelligence service and conducted anti-Soviet propaganda among the population, aiming to undermine Soviet authority and organise resistance to it." On June 17, 1939, the Military Tribunal of the Kharkov District sentenced him to ten years in prison. But two years later, in 1940, the Bolshevik authorities decided that this punishment was insufficient, and the case was sent for further investigation.

The hours of relentless interrogations began again, along with attempts to find false witnesses. Unable to bear the torture, the holy martyr Alexander passed away on 24 May 1940, in a prison hospital. Some reports claim that he was suffocated.

Burial and canonization

His burial was far from ordinary. As later recounted by one of the eyewitnesses, K.N. Krivoruchenko, the body of Archbishop Alexander was brought from the prison to the Kharkov morgue with an order to bury it. He was found in a state of complete disarray – without any clothes, his face and head shaved, and a label with the surname "Petrovsky" tied to his foot. However, almost immediately, the prison authorities issued another order to return the body to the prison, claiming that it had been delivered by mistake.

It is likely that the morgue staff would have complied if not for one of them, a former subdeacon, who recognized the archbishop. Together with another gatekeeper, who was an archimandrite, they secretly switched the label and quietly took the body of the saint. They buried him at night in the cemetery of the village of Zaliutino, dressing him in archbishop’s vestments.

The gatekeeper-archimandrite conducted the burial service. The news of the secret burial of the beloved archpastor and the location of his grave spread among the faithful, and soon the site became a place of pilgrimage.

In 1993, Archbishop Alexander of Kharkov was glorified as a local saint, and in 2000, he was canonized by the entire Church among the new martyrs and confessors.

Afterword

During the Khrushchev thaw and the de-Stalinization process, Archbishop Alexander’s case was reviewed. It was revealed that the investigator in his case was D.M. Epelbaum, an assistant chief of the 4th division of the NKVD in Kharkov, who had fabricated many criminal cases and tortured his victims during interrogations.

It was also discovered that the Renovationist "deacon" Terletsky had been a secret NKVD agent. He was used as a planted informant to accuse people he had never met. Both Epelbaum and Terletsky were arrested in 1939, during a time when the NKVD officers responsible for the purges and sending innocent people to their deaths were themselves repressed just months later.

Do the present persecutors of the Church, who imprison people based on completely absurd accusations, not realize that their turn will come too?

Those who imprison supporters of the UOC simply for being part of the true Church – do they not understand that they will have to answer for their lawlessness? Do they not fear either human judgment or God's judgment? "It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God!" (Hebrews 10:31), wrote the Apostle Paul. Were these words written just for show?

Nevertheless, this story about the holy martyr Alexander should not end here. Let us return to that moment in his life when he was drowning in the darkness of alcoholism and a life of debauchery, unable to bear the death of his mother. Many people throughout history, faced with sorrow, fall into despair. They begin to drink and get lost in the depths of sin. Many of them never recover and perish.

Archbishop Alexander could have perished as well, if not for finding the strength to rise and turn to God. And God never rejects those who come to Him. Neither drunkards, nor fornicators, nor robbers, nor anyone else. Therefore, no matter how hard life may be, no matter how tragic events may unfold, we must not despair. We must not doubt in God's mercy; we must rise and come to our Heavenly Father. Then, we will find the courage and strength to walk through life in a way that pleases the Lord. A vivid example of this is Archbishop Alexander of Kharkov.

Holy Hieromartyr Alexander, Archbishop of Kharkov, pray to God for us.