Stories of the Early Church: The place of the laity

In antiquity, a community could drive out its bishop. Why did we lose that right and turn into powerless “extras”? This is the story of the great turning point of the third century.

After describing the various ranks of church hierarchy in the first centuries of Church history, it remains to say a few words about the position and role of the laity in the life of Christian communities.

The laity – a royal priesthood. In the earliest period, all Christians understood themselves as the people of God – as disciples of Christ, men and women who responded to the call to follow Him and thus set themselves apart from pagan society. All Christians were saints, or “priests,” in the sense that all were consecrated to God.

“But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for His own possession, that you may proclaim the excellencies of Him who called you out of darkness into His marvelous light…” (1 Peter 2:9). In this awareness of the common priesthood, hierarchical and charismatic offices were seen as different forms of ministry: “There are diversities of gifts, but the same Spirit. And there are differences of ministries, but the same Lord. And there are diversities of workings, but it is the same God who works all in all” (1 Cor. 12:4–6).

The ancient Christian writers spoke about this. “Therefore form yourselves into a choir, every one of you, so that, being harmoniously tuned in unanimity, you may always… be in union with God” (Ignatius of Antioch, 2nd c.). “Neither the great without the small, nor the small without the great can exist. All of them are, as it were, bound together, and this brings benefit” (Clement of Rome, 2nd c.). Similar thoughts are found in Saints Justin, Irenaeus of Lyons, and others.

The laity took the most active and direct part in all the affairs of the community, and bishops, presbyters, and deacons did not set themselves apart as some privileged structure towering above the laity.

The number of clergy was fairly high in proportion to the total number of believers. As was already mentioned in previous publications, a Christian community consisting of only twelve people already had the right to choose a bishop for itself – and under him there was usually also a deacon, and later a certain number of presbyters as well.

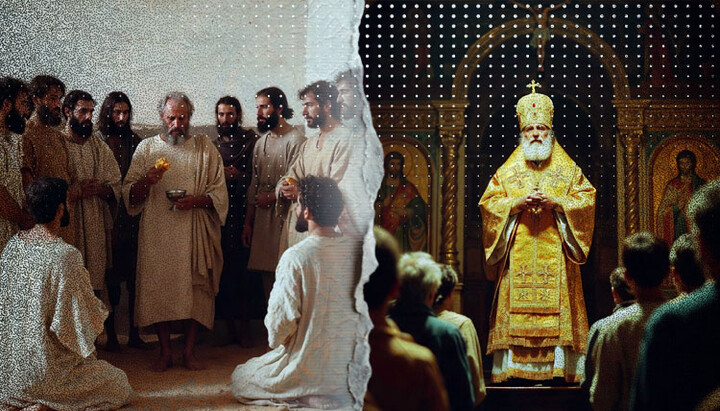

The right of choice

In the ancient Church, ordination to holy orders took place according to a basic pattern: the community (the laity) elected a candidate from among themselves, and the bishop (or neighboring bishops) ordained him. That is, bishops in principle had a right of veto – but used it very rarely.

A second-century monument, the Didache (“The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles”), instructs the community to elect its own bishops and deacons: “Appoint for yourselves bishops and deacons” (ch. 15, v. 1).

Cyprian of Carthage (3rd c.) wrote: “We know that it has been ordained by God that a priest should be chosen in the presence of the people, before the eyes of all, and that his worthiness and fitness should be confirmed by the public judgment and testimony.”

And this is by no means the same as the modern practice of ordination, when a candidate is ordained at the Liturgy in the presence of the people. In antiquity the people were not background decoration – they took the most active and direct part in the process of election.

The community’s court

The entire community had the right both to elect its clergy and to depose them. Reports of such precedents can be found in the letters of Clement, Bishop of Rome, to the Corinthians, and of Polycarp of Smyrna to the Philippians.

What is more, they speak of communities deposing men who, in the authors’ judgment, were worthy of the priesthood. Both Clement and Polycarp urge the communities to reverse these decisions, but express no doubt about the very right of the laity to act in this way.

According to the Didache, it was precisely the whole community – not only its spiritual leaders – that decided questions such as whether to receive a particular person as a true prophet and teacher or to recognize him as false, whether to allow such people to speak to the congregation, and to what extent, and so on.

The whole community also cared for its inner order and good discipline. The whole community received or did not receive visitors – that is, those Christians who came from other places for a short time or intended to remain in the community for good.

A social filter

Together the community decided whether a person had come “in the name of the Lord,” or whether he intended to abuse the hospitality of the local Christians. If the answer was positive, the community supplied him with everything necessary if he was staying only briefly. But if he wanted to remain to live there, he had to practice his trade; and if he had no regular trade, the community had to attach him to some occupation – in other words, find him work.

If, however, the visitor did not wish to work, the Didache prescribes that he should be expelled. It is noteworthy that all these questions are decided by all members of the community together, and not by the clergy alone.

Among other forms of lay participation in the life of the Church one can include their participation in church councils, the preaching of the Gospel in church gatherings, and so forth.

Another circumstance uniting clergy and people was that in antiquity, after ordination, clerics as a rule continued to earn their living by the same trade they had practiced before.

The crisis of the third century

In the third century a radical change occurred in the relationship between laity and clergy.

To this period belong both testimonies about the equality and unity of clergy and laity, and testimonies that the clergy are a higher category while the laity are subordinate and practically without rights.

And sometimes these contradictory opinions sound from the lips of one and the same author.

For example, Tertullian wrote that there is no great difference between laity and clergy: “Jesus Christ has made us priests to God, His Father. <…> Whence come the bishop and the clergy? Are they not from among all?”

The famous teacher of the Alexandrian Church, Origen, wrote that the keys by which the gates of heaven are opened are chastity and righteousness, and that they are entrusted not to priests alone but to all Christians. Addressing bishops, Origen says: “Every bishop sins against God who performs his ministry not as a slave among fellow slaves – that is, the believers – but as their lord.”

Cyprian of Carthage says that all church matters must be decided together. “Our meekness, our teaching, and our very life – that is, the life of the shepherd – require that the leaders, having gathered with the clergy in the presence of the people, should administer all things by common consent.”

Viceregents of Christ

But at the same time, in the third century we also meet the opposite testimony. A late second-century work known as the Clementines contains this assertion: “It is the bishop’s appointment to command, and the appointment of ordinary Christians to obey, for the bishop is Christ’s vicar.”

Cyprian of Carthage went very far in asserting the exclusive role of the bishop. To those who accused him of not being a true bishop, he declared that in such a case the laity who died during his episcopate would lose hope of salvation. He wrote: “To the bishop alone is authority over the Church given,” and he sought to instill fear of the clergy in the laity, threatening harsh punishments for disobedience.

In the work called the Apostolic Constitutions, whose composition is attributed to the late third century – and which the Quinisext Council (691) called “a book corrupted by heretics” – the idea of the clergy’s complete domination over the laity is advanced outright. “The shepherd is, after God, your earthly god.” It is asserted that “the laity should do nothing of themselves without the will of the bishop: even distributing gifts to the poor they must do through him.”

Earthly gods

This directly contradicts the Gospel’s words that when alms are given, the right hand should not know what the left is doing.

Which means that the authors of the Apostolic Constitutions were striving by all means – even at the cost of contradicting the Gospel – to entrench the idea of the clergy’s elevation above the people.

Here are a few more quotations from this work: “For you, a layman, it is fitting only to give, and for him, the shepherd, to distribute, for he is master and ruler of the church’s affairs. Do not demand an account from your bishop and do not watch his management: how, or when, or to whom, or where, whether well or ill, whether as he ought to manage it”; “Let them not easily trouble their ruler (that is, the bishop), but what they wish to give, let them offer through the ministers (deacons), with whom they may have greater boldness. If the laity wish to communicate anything to the bishop, let them make it known to him through the deacon as well. For even to Almighty God they come not otherwise than through Jesus.”

That is, in the third century we observe a kind of transitional period, when the idea of equality and unity of clergy and people competes with the idea of the clergy’s elevation above the flock.

The reasons for this lay not only in the clergy’s desire to obtain advantages, power, and material means, but also in the sometimes unconscious and irresponsible attitude of the people toward church affairs – fickleness of opinion, contentiousness, rivalry, and so on.

There are known cases, for example, when one part of a community elected a bishop or presbyter and another part did not accept him. Or they elected him and then rejected him; or they elected an unworthy candidate.

In the end the idea of separating the clergy and elevating them prevailed. This did not happen all at once. By the end of the third century the clergy no longer earn their living by secular occupations, but are supported by the altar. The laity, meanwhile, are gradually forbidden to preach in church. Other processes also unfold, pushing the laity away from participation in resolving the community’s affairs. This process is completed in the next, fourth century, when Christianity turns from a persecuted religion into a state religion. We will speak about this in subsequent publications on the history of the early Church.