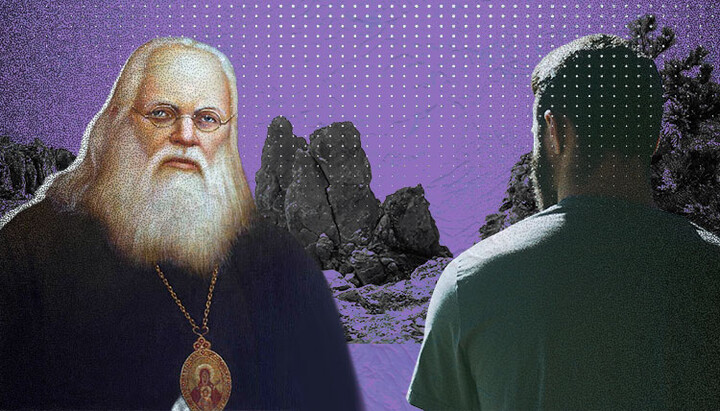

God's scalpel: A talk at the wife's coffin with Professor Voino-Yasenetsky

On the limits of human endurance, on how a saint is born from the ashes of earthly happiness, and why God operates on us without anesthesia.

Tashkent, October 1919. The city is cut off from the world by fronts and the madness of civil war; inside the house, there is a room where time has frozen by the coffin. Opposite me sits a man with a heavy gaze and the worn hands of a surgeon – Valentin Feliksovich Voino-Yasenetsky is forty-two years old, he has four children and an abyss ahead. His wife Anna, his "holy sister," has just passed away after several years of consumption.

In icons we see him in episcopal vestments, wearing a panagia, but here he is in an old jacket, and his face bears that very “stone mask” his colleagues in the hospital used to whisper about. I do not know how to begin the conversation. Words sound inappropriately loud in this silence.

When God сuts it live

– Valentin Feliksovich, you've just come from the operating room. How are you even standing after such a loss? Anyone in your place would have cursed the heavens.

He doesn't raise his eyes, his fingers work through prayer beads, but in them one feels the grip of a man accustomed to holding a clamp on the carotid artery.

– We often confuse punishment with surgery, his voice is dry as the sand of Turkestan, words come slowly, as if through pain. – I am a surgeon and I know: to save a life, one must mercilessly cut away part of the flesh, down to the healthy tissue. When Anna was dying, I felt how God was operating on my own soul without anesthesia. Because my anesthesia was her, my earthly happiness.

We are used to gentle answers, but here there is the stern logic of pain. Professor Voino-Yasenetsky finally raises his eyes; there is no rage in them – only bottomless fatigue and a strange, frightening clarity.

– Anna was a holy soul, in Chita during the Japanese War they called her holy sister not for her beautiful eyes.

She was my anchor, but I began to rely too heavily on this anchor. I loved her more than the One who created her. And the Lord in His terrible and great love removed the mediator.

In the kitchen, the children are arguing about something in half-whispers: four orphans, in 1919 in Tashkent – this is almost a death sentence: typhus, Spanish flu, starvation rations.

– For three nights I read the Psalter over her, continues the future Saint Luke. – Do you know what it means to read the Psalter over the one who was your breath? The words struck the walls and returned to me. And suddenly on the third night I reached the Song of Hannah: "The barren woman gives birth to seven, but she who has many children languishes." Do you know what I felt at that moment?

– Fear?

– No. I felt how into my mind, into my very blood God placed an answer – an illumination stronger than any scientific discovery. I understood: the "languishing mother of many" is Anna. And the "barren woman" is the solution that the Lord prepared.

Heavenly task and earthly solution

We seek miracles – for the dead to rise, for bullets to fly past, but the real miracle of Saint Luke began with the recognition of absolute helplessness.

– And then you came to Sofya Sergeevna? I ask.

– Yes, to Veletskaya, my operating room nurse. A single woman, devoted to the cause. I came and said: "God has chosen you to become a mother to my children." Without marriage, without earthly calculations, simply because that's what is needed for eternity. And she agreed. She will raise them.

A strange combination of cold calculation and burning faith. Professor Voino-Yasenetsky looks at the world as an operating field: pus is sin, the scalpel is God's will.

– People will say that you are cold-hearted, I remark. – That the day after the funeral you operated on people with the same impenetrable face.

– And what should I have done? he shrugs slightly. – Cry over the patient's wound? He's not interested in my tears, he needs my professionalism. I cannot replace Anna with another woman, it's impossible. Love cannot be replaced, it crystallizes. My widowhood is not a dead end, but the beginning of my monasticism in the world. I am betrothing myself to the Church, because on earth I no longer have a harbor.

Anatomy of faith in the fire of war

Through the surgeon's coat, the future cassock of an archbishop invisibly emerges. Saint Luke does not yet know that decades of camps await him, that he will operate in exile with a simple penknife, that he will become a laureate of the Stalin Prize and yet remain a persecuted confessor. But it was here, in Tashkent in 1919, that the main operation was performed.

– We are all now in this "operating room," I say. – War, losses, homes turned to ash. It seems to us that God has abandoned us.

– He does not abandon, Valentin Feliksovich cuts off.

He simply removes the anesthesia so that we finally wake up. So that we understand: here, on earth, we are only passing through. Our true citizenship is not in Tashkent or Kiev, but there, where Anna is now.

I step out into the cold corridor, the air smells of dust and carbolic acid. This was an honest conversation without the consoling fairy tales that people so love to tell the suffering.

Saint Luke (Voino-Yasenetsky) teaches us the courage to be honest with God. If He takes away, it means He is preparing us for something greater; if He cuts it, it means He is saving us from the gangrene of despair.

Night Tashkent darkens outside the window, and I think: holiness is not when everything is good for you, but when everything has been taken from you, and you stand and say: "Glory to You, God, for this scalpel."

We don't know what tomorrow will bring, but looking at this man in the "stone mask," you begin to understand: his strength is not in his nerves, but in his ability to give his children, his pain, and his life into the hands of the One who never makes a mistake when making an incision.

To become a lamp, one must first burn. His Anna, his "holy sister," became the fire in which Professor Valentin burned, to be resurrected as Saint Luke.