How the first days of the Church shaped the life of modern Christians

Our Church has a heavenly origin. By its very nature, it is both divine and human. Christ Himself is its Head, and since the day of Pentecost, all of us have become members of His Body in the Holy Spirit.

The foundation of the Church was laid by Jesus Christ Himself during the three and a half years of His earthly ministry. In the Gospel, we encounter not only His new teaching – the call to divine perfection: “Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Matthew 5:48) – but also His institution of the sacraments and revelation of the fundamental dogmas of faith.

It was the Lord who chose the Apostles from among the people, granting them special authority distinct from that of other followers – the authority to teach, to perform sacred rites, and the “power of the keys” to bind and to loose consciences.

The most significant event of those ten days, as recorded by the Apostle Luke in the Book of Acts, was the election of the twelfth apostle to replace the fallen Judas. The chosen one was Matthias, selected by lot, a witness of the entire earthly ministry of Jesus.

At that time, the number of Christ’s true followers can be roughly inferred from the Apostle Paul’s words that the Risen Lord “appeared to more than five hundred brethren at once” (1 Corinthians 15:6). Among them, 120 believers took part in the election of Matthias before the face of the “Lord who knows the hearts of all.”

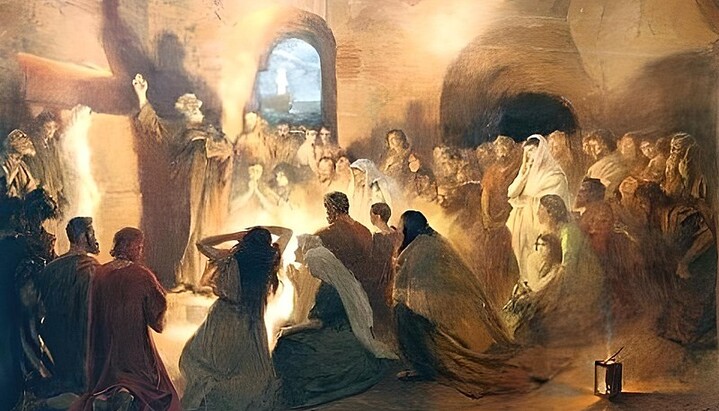

The Descent of the Holy Spirit is the birth of the Church. Christ calls the sending of the Holy Spirit “the Promise of the Father” (Luke 24:49). The coming of the Comforter is part of God’s divine plan for the salvation of the world – what theology calls “the Economy of our Salvation.” The Feast of Pentecost was foretold by the prophets of the Old Testament; the Apostle Peter himself refers to the Prophet Joel when explaining the behavior of the apostles on the day of Pentecost (see Acts 2).

There are two opinions about how many people received the Holy Spirit at that moment. According to one, the tongues of fire rested upon each of the 120 people who, a few days earlier, had participated in the election of the twelfth apostle. The other view – and the more probable one – holds that the Comforter descended upon the Twelve Apostles, since it was to them that the promise had been given, and their number had been completed by the election of Matthias precisely for this purpose.

Scripture notes that women who had come from Galilee were also with the apostles. Church Tradition, reflected in iconography, generally follows the view that the Holy Spirit descended upon the Twelve, yet also includes the Mother of God among them.

The place and time of Pentecost

Before His Ascension, the Lord commanded His disciples not to depart from Jerusalem until they were “clothed with power from on high.” Thus, Jerusalem became the city of Pentecost, fulfilling the prophecy: “For out of Zion shall go forth the law, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem” (Micah 4:2).

According to Church tradition, the descent of the Holy Spirit took place in the Upper Room on Mount Zion – near the Temple – where a large crowd had gathered, drawn to the “house of Pentecost.” The Book of Acts recounts that “tongues as of fire” descended with a sound like a mighty wind around the third hour of the day – about nine o’clock in the morning on Sunday.

The transformation of the apostles

Under the power of divine grace, the apostles were transformed. Their minds, hearts, wills, and desires were renewed. During Christ’s earthly ministry – and even at the time of His Ascension – they still expected an earthly kingdom and worldly power. We recall the request of Salome for her sons James and John, and the disputes among the disciples over who would be greatest in the kingdom.

From the moment the Comforter descended, the apostles understood everything. The promise of the Master had been fulfilled: “The Spirit of truth will guide you into all truth.” The Holy Spirit enlightened their minds to perceive the prophecies in their true sense. All their earthly and Judaic notions of the Messiah vanished. From then on, they became preachers of the Heavenly Kingdom and of the dominion of the spirit over the flesh.

Each apostle underwent a profound inner change. Those who had fled in fear in Gethsemane now became fearless heralds of the Gospel, ready to die for the truth. The Parakletos – the Comforter – filled them with grace to proclaim the Kerygma: the confession of faith in the One born in Bethlehem, crucified outside Jerusalem, foretold by the prophets – Christ, the Son of God, truly God Himself.

The essence of the apostolic message was this: the death and resurrection of Christ deliver all who believe in Him from sin, from the power of the devil, and from death itself. To enter this faith, one must live according to the commandments of the Gospel: “If anyone loves Me, he will keep My word” (John 14:23).

To equip the apostles for their mission, the Holy Spirit bestowed upon them many gifts – among them the ability to speak in diverse tongues, so that Jews from every nation marveled to hear the apostles proclaiming the wonders of God in their own languages.

The first days of the Church

The community of the apostles’ followers came to be called ekklesia – a “gathering of the people,” corresponding to the Hebrew kahal and the Slavic tserkov (“Church”). The first nucleus of the Church consisted of Galileans (cf. Luke 19:37). The opening chapter of the Acts of the Apostles – the only historical book of the New Testament – mentions a gathering of about 120 persons. Together with the Twelve, they formed the foundation of the young Church.

After the Apostle Peter’s first sermon on the day of Pentecost, when three thousand people were converted, the Church was joined by both inhabitants of Jerusalem and Jews of the diaspora. Many of the priests repented and received baptism. The Book of Acts, however, does not record any conversions from the Sanhedrin, the supreme religious authority of Judaism – for the Word of God remained closed to them. The same Sanhedrin and high priests who had condemned Christ now began persecuting His Church. The Acts even preserve the debates that took place in their council about the apostles (see Acts 5:34–39). Yet “the Lord added to the Church daily those who were being saved.”

According to tradition, the first bishop of the Jerusalem Church was James, the brother of the Lord, appointed by Christ Himself, who appeared to him after the Resurrection.

The grace of the Holy Spirit worked so powerfully that all believers lived as saints: “All who believed were together and had all things in common… and distributed to all, as anyone had need.” This communal way of life became the model for Christian monasticism. The early Christians “continued steadfastly in prayer” and in the “breaking of bread” – the Eucharist. Prayer was the breath of the early Church and remains the foundation of spiritual life for all ages. The Church grew and multiplied among the Jews, guided by the Twelve Apostles in preaching and governance.

The Sacraments – foundation of the Church

From its very beginning, the Church appeared as a community of believers in the Death and Resurrection of Christ. When those moved by Peter’s sermon asked, “What shall we do?” the Apostle, filled with the Holy Spirit, gave a clear answer: entry into the Church comes through repentance and baptism (Acts 2:38).

Thus, from the first days, the Church manifested herself as the bearer of the Sacraments. The apostles, endowed with the fullness of priestly grace, could ordain, bind and loose, preach, baptize, and celebrate the Eucharist.

Among the first converts were not only local Jews but also Hellenists – Jews of the diaspora who spoke Greek and were shaped by Greek culture. It is likely that many of them, upon returning home, became the first messengers of Christ’s Kingdom. It is telling that all seven deacons appointed by the apostles bore Greek names (see Acts 6:5), reflecting both the openness of the Hellenists to the Gospel and their vital role in the early Church.

The Jewish life of the time was steeped in the awareness of sin and the need for forgiveness – the reason rivers of animal blood flowed in the Temple. Yet every faithful Israelite understood that the blood of bulls and goats could never truly take away sin. The messianic hope of Israel, nourished by Scripture, centered on the expectation of this forgiveness from the Messiah Himself.

Tens of thousands responded to the call of John the Forerunner, the “prophet of the wilderness,” whose baptism of repentance prepared the way for the Lord. Those who received his baptism confessed their sins and washed in water. His preaching prepared the people for Christ and His baptism “with the Holy Spirit and with fire.”

The most sincere of John’s disciples noticed this and said: “He whom you baptized is now drawing more disciples than you.”

In retrospect, we see a clear divine economy of repentance: it was preached by John the Forerunner, proclaimed by Christ, taught by Him to the apostles, and begun by the apostles themselves on Pentecost: “Repent, and let every one of you be baptized” (Acts 2:38).

For all ages, the preaching of repentance has remained the core message of the Church, and the granting of forgiveness – Her central mission – until the day of the Second Coming of Christ.