Why Lviv residents once defended “Muscovite” Christmas

Today yet another pretext has been invented to destroy Orthodoxy. It is called “not a Ukrainian tradition.” But what actually constitutes tradition in Ukraine?

Celebrating the Nativity of Christ on 25 December according to the Julian calendar is now declared “not in Ukrainian traditions.” From now on it is celebrated on 12 December (25 December according to the Gregorian calendar). It is now also deemed “not in Ukrainian traditions” to celebrate the Baptism of the Lord on 6 January according to the Julian calendar (19 January Gregorian). And it is supposedly entirely “not Ukrainian” to immerse oneself in an ice hole on Theophany – something the Lviv City Council has strictly prohibited.

Yet, apparently, it is “in Ukrainian traditions” to light the largest Jewish menorah in Europe on Kyiv’s main square. It is also “in Ukrainian traditions” to replace the Christmas tree with the pagan “didukh.”

The loudest cries about “Ukrainian” and “non-Ukrainian” traditions are heard in western Ukraine and, in particular, in Lviv. But here lies the irony: in that very same Lviv, the traditions that are now somehow labeled “non-Ukrainian” were once defended by the locals with such determination that they were ready to lay down their lives rather than abandon them.

How Galicians defended Orthodox Christmas

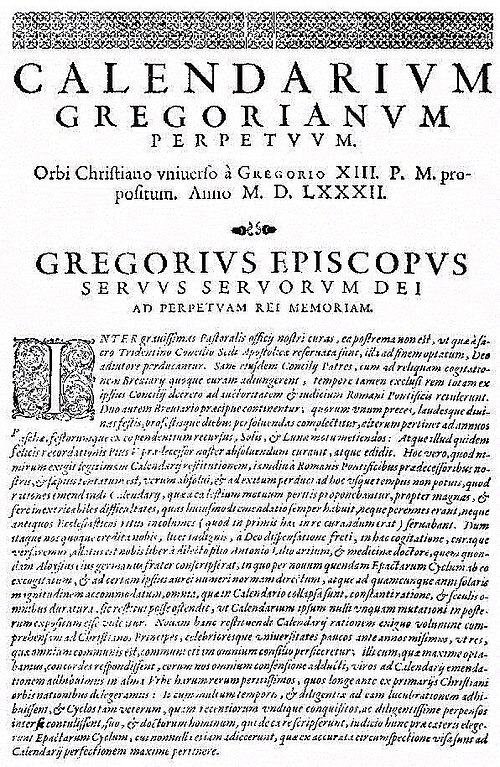

The Gregorian calendar was introduced by Pope Gregory XIII. In 1582, he issued the bull Inter gravissimas, according to which Catholics went to bed on 4 October and woke up on 15 October of that same year. In this way, the pope sought to correct the discrepancy between the Julian calendar and astronomical time, which by then amounted to ten days. By solving one problem, the Gregorian calendar created many others – but that is not our subject here.

Catholic countries accepted the innovation without protest. Orthodox and Protestant ones rejected it. The greatest difficulties arose in countries with mixed populations, among which was the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, of which Ukraine – or rather western Ukraine with its center in Lviv – formed a part.

After Pope Gregory XIII proposed that the Orthodox patriarchs synchronously adopt the new calendar, Patriarch Jeremiah II (Tranos) of Constantinople convened a council in Constantinople in 1583, which decreed the following:

“Whoever does not follow the customs of the Church and what the seven holy Ecumenical Councils decreed concerning holy Pascha and the menologion, and which they rightly established for us to follow, but instead wishes to follow the Gregorian Paschal reckoning and menologion, opposes all the definitions of the holy Councils together with the impious astronomers and seeks to change and weaken them – let him be anathematized, excommunicated from the Church of Christ and from the assembly of the faithful. But you, Orthodox and pious Christians, remain in that which you have learned, in which you were born and raised, and, when necessity demands, shed even your own blood in order to preserve the paternal faith and confession.”

In the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, according to most historians, no separate decisions of the Sejm or of King Stephen Báthory were adopted. State institutions simply switched to the new calendar de facto, on the basis of the papal bull. Orthodox and Protestant inhabitants, however, categorically refused to adopt the new reckoning of time. As early as 1583, separate decrees or letters from Stephen Báthory began to appear, addressed to cities such as Lviv, Vilnius, Riga, and others, demanding that they cease resisting the new calendar. The king was angered, writing that because of the obstinacy of Orthodox townspeople “considerable errors arise in the celebration of feasts and confusion in other daily affairs.” But the Orthodox stood firm. Then “activists” were brought into play.

On 24–25 December 1583 according to the Julian calendar (3–4 January by the new style), on Christmas, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Lviv, Jan Dymitr Solikowski, gathered his militants, armed them, and sent them on raids against Orthodox churches in Lviv.

The “activists” burst into churches during services, beat believers and clergy, threw them out into the street, and closed and sealed the churches.

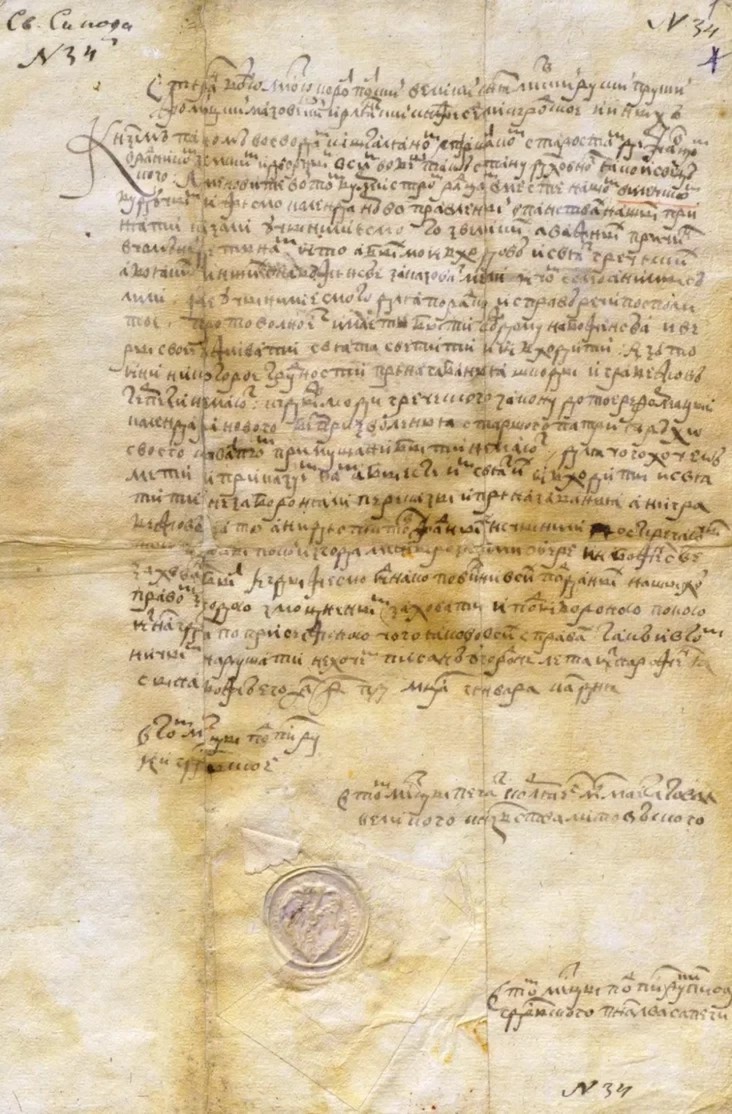

In response, the Orthodox Bishop of Lviv, Gideon (Balaban), in February 1584 filed complaints against Solikowski’s actions in the courts of Lviv and Halych (Zubrytskyi D., Chronicle of the City of Lviv, Lviv, 2006, pp. 188–189).

As a result, Orthodox Lviv residents defended their right to use the Julian calendar. In 1584–1585, Stephen Báthory sent letters to cities with a different tone altogether. In them, he urged his subjects of various confessions not to hinder one another in celebrations, services, rites, bell ringing, and so forth. One such letter was sent by King Stephen Báthory to the city authorities of Vilnius on 21 January 1584.

If the Lviv residents of the sixteenth century had learned that their descendants in the twenty-first century would call the Julian calendar a “non-Ukrainian” tradition, they would have been utterly shocked.

However, branding something as “Muscovite” and banning it on that basis is hardly a new practice.

How Galicians founded the Ruska Rada

In 1848–1849, Europe was swept by a series of revolutionary events that historians call the Spring of Nations. In the Austrian Empire, which at that time included Poland and western Ukraine, various peoples likewise demanded respect for their national traditions, language, religion, and other rights.

In Lviv, on 2 May 1848, the Main Ruska Rada was established, representing the interests of the Ukrainian population – the Rusyns, as they called themselves. Its leadership consisted entirely of Uniates. The first head of the Rada was the Uniate bishop Hryhorii Yakhymovych, and his deputy was the Uniate priest Mykhailo Kuzemskyi. The Rada included mainly representatives of the Lviv intelligentsia.

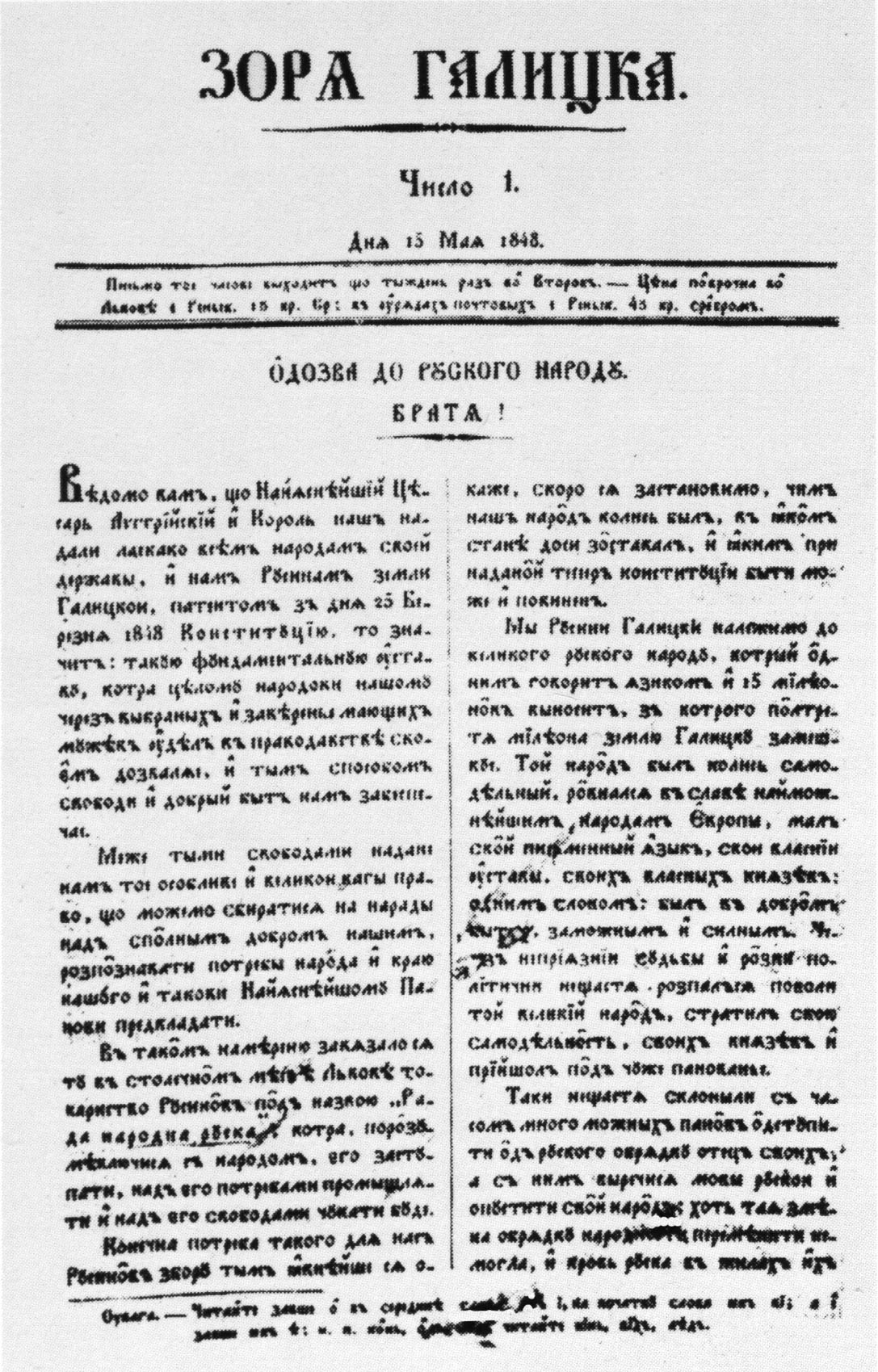

On 15 May 1848, the Rada published the first issue of the journal Zoria Halytska, which contained an Address to the “Ruskyi people.”

For today’s realities, it sounds unbelievable, but in this document the Lviv Uniates identified themselves and the entire population of Galicia as follows: “We, the Galician Rusyns, belong to the great Russian people…”

In the Address, the authors demanded equal rights for the Ruskyi (in modern terms, Ukrainian) people, the development of the Ruskyi language (the Galician variant of Ukrainian), respect for religion and culture, and so on. Overall, it is a highly interesting historical document.

But the Poles wanted no rights for the Galician Rusyns – that is, for Ukrainians. They sought to pursue a policy of Polonization in the Austrian Empire just as they had in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. And what argument do you think they advanced against granting rights to the Galician Rusyns? A very simple one – they called them Muscovites. And the Ruska Rada, accordingly, was branded as Moscow narratives.

In March 1848, the Poles gathered to write their own address to the Austrian emperor, demanding autonomy for themselves, and they wanted representatives of the Rusyns to sign it as well. When the latter refused, the Poles declared the following: “There are no Rusyns here (that is, in Galicia – author). This is a traitor – a Muscovite!” (Stefan Kaczała, Polityka Polaków względem Rusi, Lviv, 1879, p. 286).

Conclusions

First, the Julian calendar, Orthodox Christmas, Orthodox rites, and traditions are as genuinely Ukrainian as it gets. The ancestors of today’s Lviv residents and Galicians – not to mention those of central and eastern Ukraine – preserved all this strictly and fought for their rights. By contrast, they regarded the Gregorian calendar as an alien innovation. The same applies to Catholic traditions, in many cases even after the Union of Brest in 1596.

Second, the inhabitants of western Ukraine did not hesitate to call themselves Russians or Rusyns, their language Russian, and their national body the Ruska Rada. Why, then, have we today voluntarily and without resistance ceded to Muscovites (Russians) the right to the name “Russian”? Why do we persecute our own fellow citizens for speaking Russian?

And third, arguments such as “this is not a Ukrainian tradition,” “this is Muscovite,” “these are Kremlin narratives,” and the like have been used for a very long time already.