Typikon: The rulebook few have read, yet everyone follows

It is rarely read, even more rarely understood, and at best followed in fragments. What do we need to know about the Church’s principal liturgical book to serve not by the letter, but in spirit?

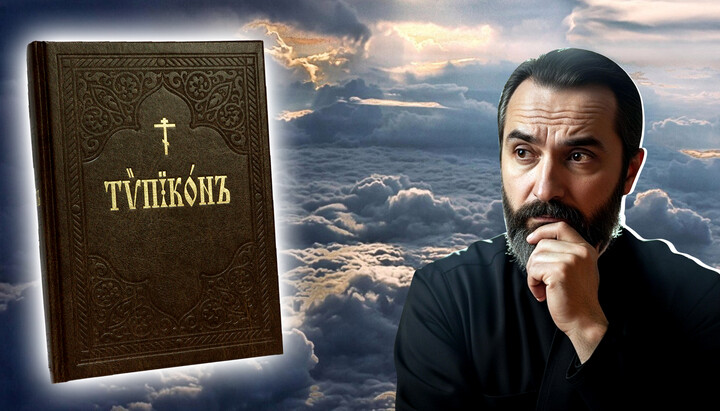

The Typikon is a paradoxical book. On one hand, it forms the foundation of the entire liturgical life of the Church; on the other, even among clergy and ecclesiastical rubrics experts, it’s rare to find someone who has actually read it or knows how to use it properly. It governs the discipline of fasting and the structure of the liturgical year, yet remains largely unknown.

Many of its prescriptions have either lost relevance, are hardly practiced, or have become so formalized that they no longer reflect the inner logic of the rule. Few stop to ask: how can we serve not by the letter, but by the spirit?

It is impossible to address all the nuances of Typikon application in a single article. So today, we begin with a brief overview of the book’s history and structure.

Even at this stage it becomes clear: to apply the Typikon wisely and responsibly, one must not simply know the rules, but understand their meaning and be able to discern what in worship is essential, and what is secondary.

In future articles, we will continue exploring the Typikon, gradually uncovering which elements stem from historical traditions, which are local disciplines of specific monasteries, and which are expressions of the living, universal experience of the Church.

Many rules, one Typikon

Let’s begin with the fact that the Typikon is not the only rule of its kind. Written rules began appearing alongside the rise of monasticism. Each major monastery or group of monasteries had its own rule – its own order of services, fasting practices, daily routines, and behavioral norms.

The well-known proverb, “Don’t bring your own rule to another’s monastery,” reflects the historical reality of Church life for centuries.

Parish churches also had their own local customs, but only monasteries – being centers of learning and literacy – had the capacity to create written statutes. This is why we have almost no surviving typika from parish churches, despite scattered references to local variations.

One must understand that the ancient monastic communities of Palestine or Egypt were not small groups – they were monastic cities with hundreds or even thousands of inhabitants. They needed a legal structure to regulate daily life, property, worship, and discipline.

Among the most notable early monastic rules are:

- The Rule of St. Pachomius the Great (c. 318) for his monastery in Tabennisi (Egypt),

- The Great Asketikon of St. Basil the Great,

- The Institutes of St. John Cassian,

- The Rule of St. Benedict of Nursia (6th century).

The most developed and influential was the rule of the Lavra of St. Sabbas the Sanctified near Jerusalem – hence its name, the Jerusalem Typikon. After the Persian and later Arab conquests of Palestine in the 7th century, church life was disrupted, and the original Typikon was lost, though preserved in various edited forms.

Another major center of church life was Constantinople. Its most prominent monastery was the Studion Monastery. The Studite Rule was somewhat simpler, with lighter fasts. There was also a distinct Patriarchal Rule of the Great Church of Constantinople, known for its solemnity. It significantly influenced the Athonite Rule, which was later brought to Rus’ by St. Theodosius of the Caves and became the foundation for both monastic and parish practice.

This was not the end of its development. After the fall of Byzantium, the Studite Rule was universally replaced by the Jerusalem Rule – a transition that occurred in Rus’ beginning in the 14th century.

Thus, the rule followed in our Church today is the result of a long historical process, woven together from Byzantine, Studite, Athonite, and Jerusalem traditions.

A note on etymology

Today, the principal rulebook is known to us as the Typikon, whose full title is: “The Typikon, that is, the depiction of church services in Jerusalem, at the most holy lavra of our venerable and God-bearing father Sabbas…”

It’s telling how the authors described their works: St. Sabbas called his: “Model, Tradition, and Law”, St. Theodore the Studite used “Image” – indicating the reflection of a higher design in earthly order.

All of these titles stem from the Greek word τύπος (typos) – meaning type, form, or model. Later, the word took on the meaning of a law or regulation, but at its heart, Τυπικόν means “that which is formed according to a model.”

This concept of Typikon as a model is central to its meaning. It points toward an ideal, a heavenly order that – like the Gospel itself – cannot be fulfilled in its entirety but remains the image to which we strive.

The Typikon offers not just rules, but the logic and structure of a divine liturgical pattern.

Can a monastic rule be applied in a parish?

It must be remembered that the Typikon adopted by our Church is, in origin, a monastic rule. It contains instructions such as when to lay aside staffs, how to wake monks, how to labor in obedience, and how to behave in the refectory.

It was crafted for organizing the life of a monastic community within specific historical, climatic, and cultural conditions. It was never intended for use by laypeople in parish settings. Nevertheless, it has become the standard across both monastic and parish life, inevitably creating tension between its expectations and the practical capabilities of modern parish life.

Thus, while the Typikon regulates our practice only conditionally, it remains a great monument of liturgical thought. There is an increasing recognition of the need for a relevant liturgical rule that reflects the realities of today’s Church life.

This is not about dismantling tradition, but about continuing it with understanding – because the Church does not exist for the Typikon, but the Typikon exists for the Church.

Such a process is only possible with maturity, knowledge, theological literacy, and liturgical awareness on the part of both clergy and laity. That is why we must study the Typikon attentively and thoughtfully – as a living tradition of the Church.