Veneration of relics: How not to slip into paganism

In light of the ongoing campaign to open and examine the relics of the Pechersk saints, it is worth reflecting on what relics truly mean to us and revisiting Orthodox teaching on the bodies of the departed.

At the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, biologists and veterinarians continue their “examinations” of the relics of the Pechersk saints. The Holy Mountain of Athos, along with churches in Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Jerusalem, has already condemned these actions as blasphemous. This is not merely a gesture of “corporate solidarity”; the desecration of saints’ relics is a profound tragedy for Christians.

Yet this disturbing situation also raises a question for all of us: How do we, as Christians, relate to holy relics?

An earlier article on UOJ discussed why Christians venerate relics, gave a brief historical overview, and provided theological justification. However, it did not touch on an equally important topic – the distortion of proper Christian veneration into what could be called "Orthodox ritual paganism." Unfortunately, this has occurred throughout Church history and, in some cases, continues today.

Iconoclasm, which also targeted the veneration of relics, did not arise in a vacuum. It was a reaction to genuine pagan attitudes toward icons and relics that had come to dominate the Church. From the 4th century onward, after Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, many converts joined the Church without abandoning their pagan worldview.

They simply brought that worldview into the Church.

Icons and relics began to be treated as magical objects, endowed with inherent supernatural power.

St. John Chrysostom (4th century) wrote: “Many, touching the graves of martyrs, think that this alone will save them. But if your life is evil, neither relics, nor icons, nor crosses will help you!”

St. Maximus the Confessor (7th century), writing just before the iconoclastic period, observed: “Those who venerate icons but lack the fear of God and love in their hearts are bowing to wood and paint just as pagans once bowed to idols.”

The Seventh Ecumenical Council (787) affirmed the veneration of icons and relics and defined a proper attitude toward them. But sadly, superstitions and pagan thinking did not disappear – they only grew. In the medieval West, such attitudes became dominant.

For example, instead of purifying the soul from passions and uniting with God through the Eucharist and prayer, people obsessed over the Holy Grail – the cup used by Christ at the Last Supper. Medieval elites believed that anyone who drank from it would receive forgiveness of sins, eternal life, immortality, and even material wealth. The legendary Knights of the Round Table devoted their lives to seeking this cup – fighting, killing, and dying for an object that most likely never survived and, even if it did, has no salvific significance. To this day, around six or seven cathedrals claim to house "the" Holy Grail.

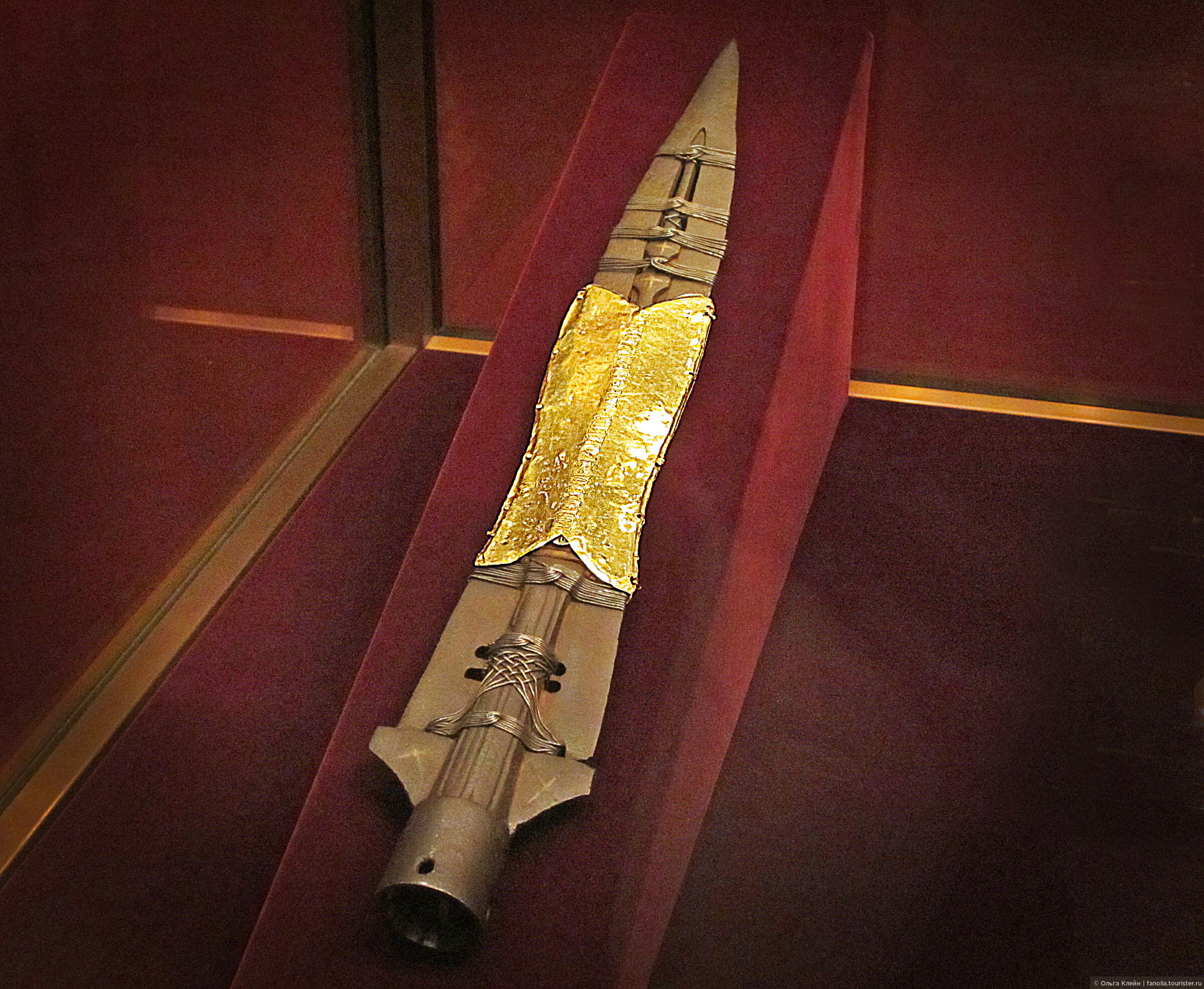

Similarly, warriors sought the “Spear of Longinus,” said to have pierced Christ’s side. Although the first mention of it appears only in the 6th century and it has no spiritual significance in the Gospel, it was believed that whoever possessed the spear had divine favor and military supremacy. One such spear – the so-called "Vienna Lance" – became a symbol of imperial authority in the Holy Roman Empire and is still kept in the treasury of Vienna's Hofburg Palace. So, whoever holds the spear is the king. But what does that have to do with the teachings of Christ? Incidentally, today, in addition to the Vienna Lance, there are three more such spears.

The same happened with relics. Owning relics became prestigious – a mark of power and sanctity. In today’s terms, if billionaires must own a jet, yacht, and football club, in the Middle Ages, relics were the ultimate “must-have.” They were stolen, fought over, and bought – demand created supply.

Enter the charlatans, including some at the highest Vatican levels, who fabricated relics and invented elaborate legends to support their authenticity. Today, about seven churches claim to house the head of John the Baptist. Even if we assume each has only a fragment, the total would still make up several heads. Two heads are claimed to belong to the Apostle Mark – one in Venice, the other in Alexandria. Countless other examples exist.

It’s well known that the relics of St. Nicholas were “transferred” to Bari in 1087 – in truth, they were stolen. Less known is that nine years later, Venetians arrived to take relics for themselves and, finding the tomb empty, took some bones from the crypt – possibly belonging to another Nicholas, a relative of the saint. This sparked a centuries-long rivalry between Bari and Venice, both claiming the “true” St. Nicholas. It’s hard to imagine anything more offensive to the saint than Christians fighting over his remains.

“You venerate the relics of saints, yet live impiously? Do you really think the saint approves of your deeds?” – St. John Chrysostom

Such attitudes are not confined to the distant past. Consider a modern example: On the night of December 20–21, 2023, Moscow’s nightclub “Mutabor” hosted a notorious nude party, sparking public outrage – especially amid a wartime narrative about “Holy Russia.” In the aftermath, organizers scrambled to do damage control. One of them, nightclub owner Vladimir Danilov, was soon pictured in a church handing over supposed relics of St. Nicholas – allegedly purchased from the Vatican with a certificate of authenticity.

Independent investigations, including by Radio Svoboda, revealed the relics were fake. But that no longer mattered. The photo-op was successful: “We oppose darkness and evil; we support the Church.” Even if the relics had been authentic, would this not still be a sacrilegious display disguised as piety?

This obsessive desire for sacred artifacts – believing they bring eternal life, power, or success – has led to absurdities. Some items venerated as relics include:

- Hairs from Jesus’s beard

- The swaddling clothes of Christ

- The “Holy Foreskin” of the infant Jesus

- The blood of John the Baptist

- Hair from the Virgin Mary

- A milk tooth of the Virgin Mary

- The Virgin Mary’s milk

Russian tsars were reportedly blessed with the Virgin’s milk. These relics often "surfaced" after centuries – and always in convenient places. For example, the “Holy Foreskin” appeared in 800 AD just in time for Charlemagne to gift it to Pope Leo III in exchange for imperial coronation. Today, 18 such foreskins are claimed by various churches.

So how can we distinguish true Christian veneration from paganism? Where is the line between reverence and superstition, between sanctity and magical thinking?

It is not always easy to draw that line, but several key principles differentiate Christian faith from paganism:

1. The source of grace is God, not the relics themselves.

“Power is not in the relics, but in the One who glorified them,” wrote Blessed Augustine (4th–5th c.). God may choose to grant grace through relics or by any other means. What matters most is living by God’s commandments, striving for holiness, loving God and neighbor. Venerating relics without repentance and obedience is not Christian faith – it is magical thinking.

2. True veneration means imitating the saint’s life and virtues.

This was affirmed by Augustine and many other Church Fathers. “The power of saints lies not in their dust, but in faith and good deeds. Whoever seeks miracles without imitating the saints is closer to pagans than to Christ” – St. Ephraim the Syrian.

3. We seek the saints’ help primarily in our struggle against sin.

Turning to them only for healing, success, or material gain reflects a consumerist, not Christian, mindset. Of course, it's fine to ask saints for help in daily life, but above all we must desire union with God.

4. Possessing relics should not be a source of pride – nor lacking them a cause for envy.

It is wrong to boast that our church or monastery has relics, or to strive to obtain them merely to “keep up with others.” Turning relics into profitable “faith-based business projects” is as inappropriate now as it was in the Middle Ages.

“But seek first the Kingdom of God and His righteousness, and all these things shall be added to you” (Matthew 6:33).

If we live by this teaching, the saints will help us – both in our journey toward the Kingdom and in all that is added along the way.

All saints who pleased God, pray to Him for us.